Pseudomonas aeruginosa

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | |

|---|---|

|

|

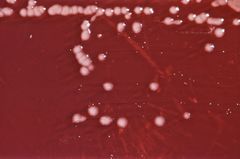

| P. aeruginosa on an XLD agar plate. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Proteobacteria |

| Class: | Gamma Proteobacteria |

| Order: | Pseudomonadales |

| Family: | Pseudomonadaceae |

| Genus: | Pseudomonas |

| Species: | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Schröter 1872) Migula 1900 |

|

| Type strain | |

| ATCC 10145 CCUG 551 |

|

| Synonyms | |

|

Bacterium aeruginosum Schroeter 1872 |

|

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common bacterium which can cause disease in humans and non-human animals. It is found in soil, water, skin flora, and most man-made environments throughout the world. It thrives not only in normal atmospheres, but also in non oxygenated atmospheres, and has thus colonized many natural and artificial environments. It uses a wide range of organic material for food; in animals, the versatility enables the organism to infect damaged tissues or people with reduced immunity. The symptoms of such infections are generalized inflammation and sepsis. If such colonizations occur in critical body organs such as the lungs, the urinary tract, and kidneys, the results can be fatal.[1] Because it thrives on most surfaces, this bacterium is also found on and in medical equipment including catheters, causing cross infections in hospitals and clinics. It is implicated in hot-tub rash. It is also able to decompose hydrocarbons and has been used to break down tarballs and oil from oil spills.[2][3]

Contents |

Identification

It is a Gram-negative, aerobic, rod-shaped bacterium with unipolar motility.[4] An opportunistic human pathogen, P. aeruginosa is also an opportunistic pathogen of plants.[5] P. aeruginosa is the type species of the genus Pseudomonas (Migula ).[6]

P. aeruginosa secretes a variety of pigments, including pyocyanin (blue-green), pyoverdine (yellow-green and fluorescent), and pyorubin (red-brown). King, Ward, and Raney developed Pseudomonas Agar P (aka King A media) for enhancing pyocyanin and pyorubin production and Pseudomonas Agar F (aka King B media) for enhancing fluorescein production.[7]

P. aeruginosa is often preliminarily identified by its pearlescent appearance and grape-like or tortilla-like odor in vitro. Definitive clinical identification of P. aeruginosa often includes identifying the production of both pyocyanin and fluorescein, as well as its ability to grow at 42°C. P. aeruginosa is capable of growth in diesel and jet fuel, where it is known as a hydrocarbon-utilizing microorganism (or "HUM bug"), causing microbial corrosion.[3] It creates dark gellish mats sometimes improperly called "algae" because of their appearance.

Although classified as an aerobic organism, P. aeruginosa is considered by many as a facultative anaerobe, as it is well adapted to proliferate in conditions of partial or total oxygen depletion. This organism can achieve anaerobic growth with nitrate as a terminal electron acceptor, and, in its absence, it is also able to ferment arginine by substrate-level phosphorylation. Adaptation to microaerobic or anaerobic environments is essential for certain lifestyles of P. aeruginosa, for example, during lung infection in cystic fibrosis patients, where thick layers of alginate surrounding bacterial mucoid cells can limit the diffusion of oxygen.[8][9][10][11][12]

Nomenclature

- The word Pseudomonas means false unit, from the Greek pseudo- (Greek: ψευδο, false) and monas (Latin: monas, from Greek: μονος, a single unit). The stem word mon was used early in the history of microbiology to refer to germs, e.g., Kingdom Monera.

- The species name aeruginosa is a Latin word meaning copper rust, as seen with the oxidized copper patina on the Statue of Liberty. This also describes the blue-green bacterial pigment seen in laboratory cultures of the species. This blue-green pigment is a combination of two metabolites of P. aeruginosa, pyocyanin (blue) and pyoverdine (green), which impart the blue-green characteristic color of cultures. Pyocyanin biosynthesis is regulated by quorum sensing as in the biofilms associated with colonization of the lungs in cystic fibrosis patients. Another assertion is that the word may be derived from the Greek prefix ae- meaning"old or aged, and the suffix ruginosa means wrinkled or bumpy.[13]

- The derivations of pyocyanin and pyoverdine are of the Greek, with pyo-, meaning pus, cyanin, meaning blue, and verdine, meaning green. Pyoverdine in the absence of pyocyanin is a fluorescent-yellow color.

Genomic diversity

The G+C-rich Pseudomonas aeruginosa chromosome consists of a conserved core and a variable accessory part. The core genomes of P. aeruginosa strains are largely collinear, exhibit a low rate of sequence polymorphism, and contain few loci of high sequence diversity, notably the pyoverdine locus, the flagellar regulon, pilA, and the O-antigen biosynthesis locus. Variable segments are scattered throughout the genome, of which about one-third are immediately adjacent to tRNA or tmRNA genes. The three known hot spots of genomic diversity are caused by the integration of genomic islands of the pKLC102 / PAGI-2 family into tRNALys or tRNAGly genes. The individual islands differ in their repertoire of metabolic genes, but share a set of syntenic genes which confer their horizontal spread to other clones and species. Colonization of atypical disease habitats predisposes to deletions, genome rearrangements, and accumulation of loss-of-function mutations in the P. aeruginosa chromosome. The P. aeruginosa population is characterized by a few dominant clones widespread in disease and environmental habitats. The genome is made up of clone-typical segments in core and accessory genome and of blocks in the core genome with unrestricted gene flow in the population.[14]

Cell-surface polysaccharides

Cell-surface polysaccharides play diverse roles in the bacterial lifestyle. They serve as a barrier between the cell wall and the environment, mediate host-pathogen interactions, and form structural components of biofilms. These polysaccharides are synthesized from nucleotide-activated precursors, and, in most cases, all the enzymes necessary for biosynthesis, assembly, and transport of the completed polymer are encoded by genes organized in dedicated clusters within the genome of the organism. Lipopolysaccharide is one of the most important cell-surface polysaccharides, as it plays a key structural role in outer membrane integrity, as well as being an important mediator of host-pathogen interactions. The genetics for the biosynthesis of the so-called A-band (homopolymeric) and B-band (heteropolymeric) O antigens have been clearly defined, and much progress has been made toward understanding the biochemical pathways of their biosynthesis. The exopolysaccharide alginate is a linear copolymer of β-1,4-linked D-mannuronic acid and L-glucuronic acid residues, and is responsible for the mucoid phenotype of late-stage cystic fibrosis disease. The pel and psl loci are two recently-discovered gene clusters which also encode exopolysaccharides found to be important for biofilm formation. Rhamnolipid is a biosurfactant whose production is tightly regulated at the transcriptional level, but the precise role that it plays in disease is not well understood at present. Protein glycosylation, particularly of pilin and flagellin, is a recent focus of research by several groups, and it has been shown to be important for adhesion and invasion during bacterial infection.[14]

Pathogenesis

An opportunistic, nosocomial pathogen of immunocompromised individuals, P. aeruginosa typically infects the pulmonary tract, urinary tract, burns, wounds, and also causes other blood infections.[15]

Hospital Infections

| Hospital Infections | Details and Common Associations | High-Risk Groups |

|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia | Diffuse bronchopneumonia | Cystic fibrosis patients |

| Septic shock | Associated with skin lesion ecthyma gangerenosum | Neutropenic patients |

| Urinary tract infection | Urinary tract catheterisation | |

| Gastrointestinal infection | Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) | NEC especially in premature infants and neutropaenic cancer patients |

| Skin and soft tissue infections | Haemorrhage and necrosis | Burns victims and patients with wound infections |

It is the most common cause of infections of burn injuries and of the external ear (otitis externa), and is the most frequent colonizer of medical devices (e.g., catheters). Pseudomonas can, in rare circumstances, cause community-acquired pneumonias,[16] as well as ventilator-associated pneumonias, being one of the most common agents isolated in several studies.[17] Pyocyanin is a virulence factor of the bacteria and has been known to cause death in C. elegans by oxidative stress. However, research indicates that salicylic acid can inhibit pyocyanin production.[18] One in ten hospital-acquired infections are from Pseudomonas. Cystic fibrosis patients are also predisposed to P. aeruginosa infection of the lungs. P. aeruginosa may also be a common cause of "hot-tub rash" (dermatitis), caused by lack of proper, periodic attention to water quality. The most common cause of burn infections is P. aeruginosa. Pseudomonas is also a common cause of post-operative infection in radial keratotomy surgery patients. The organism is also associated with the skin lesion ecthyma gangrenosum. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is frequently associated with osteomyelitis involving puncture wounds of the foot, believed to result from direct inoculation with P. aeruginosa via the foam padding found in tennis shoes.

Toxins

P. aeruginosa uses the virulence factor exotoxin A to ADP-ribosylate eukaryotic elongation factor 2 in the host cell, much as the diphtheria toxin does. Without elongation factor 2, eukaryotic cells cannot synthesize proteins and necrose. The release of intracellular contents induces an immunologic response in immunocompetent patients. In addition Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses an exoenzyme, ExoU, which degrades the plasma membrane of eukaryotic cells, leading to lysis.

Triggers

It has been found that with low phosphate levels, P. aeruginosa is activated from benign symbiont to express lethal toxins inside the intestinal tract and severely damage or kill the host, which can be mitigated by providing excess phosphate instead of antibiotics.[19]

Plant Disease

With plants, P. aeruginosa induces symptoms of soft rot with Arabidopsis thaliana (Thale cress) and Lactuca sativa (Lettuce).[20][21] It is a powerful pathogen with Arabidopsis thaliana[22] and with some animals: Caenorhabditis elegans,[23][24] Drosophila[25] and Galleria mellonella.[26] The associations of virulence factors are the same for vegetal and animal infections.[20][27]

Quorum sensing

Regulation of gene expression can occur through cell-cell communication or quorum sensing (QS) via the production of small molecules called autoinducers. QS is known to control expression of a number of virulence factors. Another form of gene regulation which allows the bacteria to rapidly adapt to surrounding changes is through environmental signaling. Recent studies have discovered that anaerobiosis can significantly impact the major regulatory circuit of QS. This important link between QS and anaerobiosis has a significant impact on production of virulence factors of this organism.[14]

Biofilms and treatment resistance

Biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa can cause chronic opportunistic infections. These kinds of infections are a serious problem for medical care in industrialized societies; especially for immunocompromised patients and the elderly. They often cannot be treated effectively with traditional antibiotic therapy. Biofilms seem to protect these bacteria from adverse environmental factors. Pseudomonas aeruginosa can cause nosocomial infections and is considered a model organism for the study of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Researchers consider it important to learn more about the molecular mechanisms which cause the switch from planktonic growth to a biofilm phenotype and about the role of inter-bacterial communication in treatment-resistant bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This should contribute to better clinical management of chronically infected patients, and should lead to the development of new drugs.[14]

Diagnosis

Depending on the nature of infection, an appropriate specimen is collected and sent to a bacteriology laboratory for identification. First, a Gram stain is performed, which should show Gram negative rods with no particular arrangement. Then, if the specimen is pure, the organism is grown on MacConkey agar plate to produce colorless colonies (as it does not ferment lactose); but, if the specimen is not pure, then the use of a selective plate is essential. Cetrimide agar has been traditionally used for this purpose. When grown on it, P. aeruginosa may express the exopigment pyocyanin, which is blue-green in color, and the colonies will appear flat, large, and oval. It also has a characteristic fruity smell. P. aeruginosa is catalase+, oxidase+, nitrase+, and lipase+. When grown on TSI medium, it has a K/K profile, meaning that the medium will not change color. Finally, serology could help, which is based on H & O antigens.

Treatment

P. aeruginosa is frequently isolated from non-sterile sites (mouth swabs, sputum, and so forth), and, under these circumstances, it often represents colonisation and not infection. The isolation of P. aeruginosa from non-sterile specimens should, therefore, be interpreted cautiously, and the advice of a microbiologist or infectious diseases physician/pharmacist should be sought prior to starting treatment. Often no treatment is needed.

When P. aeruginosa is isolated from a sterile site (blood, bone, deep collections), it should be taken seriously, and almost always requires treatment.

P. aeruginosa is naturally resistant to a large range of antibiotics and may demonstrate additional resistance after unsuccessful treatment, particularly through modification of a porin. It should usually be possible to guide treatment according to laboratory sensitivities, rather than choosing an antibiotic empirically. If antibiotics are started empirically, then every effort should be made to obtain cultures, and the choice of antibiotic used should be reviewed when the culture results are available.

Phage therapy against ear infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa was reported in the journal Clinical Otolaryngology in August 2009[28]

Antibiotics that have activity against P. aeruginosa include:

- aminoglycosides (gentamicin, amikacin, tobramycin);

- quinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin)

- cephalosporins (ceftazidime, cefepime, cefoperazone, cefpirome, but not cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime)

- antipseudomonal penicillins: ureidopenicillins and carboxypenicillins (piperacillin, ticarcillin: P. aeruginosa is intrinsically resistant to all other penicillins)

- carbapenems (meropenem, imipenem, doripenem, but not ertapenem)

- polymyxins (polymyxin B and colistin)[29]

- monobactams (aztreonam)

These antibiotics must all be given by injection, with the exception of fluoroquinolones and of aerosolized tobramycin. For this reason, in some hospitals, fluoroquinolone use is severely restricted in order to avoid the development of resistant strains of P. aeruginosa. In the rare occasions where infection is superficial and limited (for example, ear infections or nail infections), topical gentamicin or colistin may be used.

There has been some research success with treating mice with phage therapy, raising the survival rate from 6% to 22-87%.[30]

Antibiotic resistance

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a highly relevant opportunistic pathogen. One of the most worrisome characteristics of P. aeruginosa is its low antibiotic susceptibility. This low susceptibility is attributable to a concerted action of multidrug efflux pumps with chromosomally-encoded antibiotic resistance genes (e.g. mexAB, mexXY etc.[31]) and the low permeability of the bacterial cellular envelopes. In addition to this intrinsic resistance, P. aeruginosa easily develops acquired resistance either by mutation in chromosomally-encoded genes or by the horizontal gene transfer of antibiotic resistance determinants. Development of multidrug resistance by P. aeruginosa isolates requires several different genetic events including acquisition of different mutations and/or horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes. Hypermutation favours the selection of mutation-driven antibiotic resistance in P. aeruginosa strains producing chronic infections, whereas the clustering of several different antibiotic resistance genes in integrons favors the concerted acquisition of antibiotic resistance determinants. Some recent studies have shown that phenotypic resistance associated to biofilm formation or to the emergence of small-colony variants may be important in the response of P. aeruginosa populations to antibiotics treatment.[14]

Phosphate trigger

Phosphate has been implicated in pathogenesis of P. aeruginosa which is normally benign. Phosphate is required by the bacteria for normal functioning, and has been shown in experiments on two very different organisms to turn on its host.[19]

Prevention

Medical-grade honey may reduce colonization of many pathogens including Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[32] Probiotic prophylaxis may prevent colonization and delay onset of pseudomonas infection in an ICU setting.[33] Immunoprophylaxis against pseudomonas is being investigated.[34]

See also

- Bacteriological water analysis

- Contamination control

- Nosocomial infection

- Phage therapy

References

- ↑ Balcht, Aldona & Smith, Raymond (1994). Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: Infections and Treatment. Informa Health Care. pp. 83–84. ISBN 0-8247-9210-6.

- ↑ A. Y. Itah and J. P. Essien, Growth Profile and Hydrocarbonoclastic Potential of Microorganisms Isolated from Tarballs in the Bight of Bonny, Nigeria, World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, Volume 21, Numbers 6-7, October, 2005, doi 10.1007/s11274-004-6694-z, p 1317-1322

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 AVI Biopharma (2007-01-18). "Antisense antibacterial method and compound". World Intellectual Property Organization. http://www.wipo.int/pctdb/en/wo.jsp?IA=US2006027522&DISPLAY=DESC. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Iglewski BH (1996). Pseudomonas. In: Baron's Medical Microbiology (Baron S et al., eds.) (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ Anzai, et al.; Kim, H; Park, JY; Wakabayashi, H; Oyaizu, H (2000, Jul). "Phylogenetic affiliation of the pseudomonads based on 16S rRNA sequence". Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 50 (Pt 4): 1563–89. PMID 10939664.

- ↑ King EO, Ward MK, Raney DE (1954). "Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin.". J Lab Clin Med 44 (2): 301–7. PMID 13184240.

- ↑ Collins FM (1955). "Effect of aeration on the formation of nitrate-reducing enzymes by P. aeruginosa". Nature 175 (4447): 173–4. doi:10.1038/175173a0. PMID 13235841.

- ↑ Hassett DJ (1996). "Anaerobic production of alginate by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: alginate restricts diffusion of oxygen". J. Bacteriol. 178 (24): 7322–5. PMID 8955420.

- ↑ Worlitzsch D, Tarran R, Ulrich M, et al. (2002). "Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients". J. Clin. Invest. 109 (3): 317–25. doi:10.1172/JCI13870. PMID 11827991.

- ↑ Cooper M, Tavankar GR, Williams HD (2003). "Regulation of expression of the cyanide-insensitive terminal oxidase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa". Microbiology 149 (Pt 5): 1275–84. doi:10.1099/mic.0.26017-0. PMID 12724389.

- ↑ Williams HD, Zlosnik JE, Ryall B (2007). "Oxygen, cyanide and energy generation in the cystic fibrosis pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa". Adv. Microb. Physiol. 52: 1–71. doi:10.1016/S0065-2911(06)52001-6. PMID 17027370.

- ↑ Brown, RW (1956). Composition of Scientific Words. Smithsonian Institutional Press. ISBN 0-87474-286-2.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Cornelis P (editor). (2008). Pseudomonas: Genomics and Molecular Biology (1st ed.). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-19-6. ISBN 1904455190. http://www.horizonpress.com/pseudo.

- ↑ Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology

- ↑ Fine MJ, Smith MA, Carson CA, et al. (1996). "Prognosis and outcomes of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. A meta-analysis". JAMA 275 (2): 134–41. doi:10.1001/jama.275.2.134. PMID 8531309.

- ↑ Diekema DJ, Pfaller MA, Jones RN, et al. (1999). "Survey of bloodstream infections due to gram-negative bacilli: frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in the United States, Canada, and Latin America for the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997". Clin. Infect. Dis. 29 (3): 595–607. doi:10.1086/598640. PMID 10530454.

- ↑ Prithiviraj B, Bais H, Weir T, Suresh B, Najarro E, Dayakar B, Schweizer H, Vivanco J (2005). "Down regulation of virulence factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by salicylic acid attenuates its virulence on Arabidopsis thaliana and Caenorhabditis elegans.". Infect Immun 73 (9): 5319–28. doi:10.1128/IAI.73.9.5319-5328.2005. PMID 16113247.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 University of Chicago Medical Center (2009-04-14). "Research could lead to new non-antibiotic drugs to counter hospital infections". Press release. http://news.uchicago.edu/news.php?asset_id=1589. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Rahme LG, Stevens EJ, Wolfort SF, Shao J, Tompkins RG, Ausubel FM (1995). "Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals". Science 268 (5219): 1899–902. doi:10.1126/science.7604262. PMID 7604262.

- ↑ Rahme LG, Tan MW, Le L, et al. (1997). "Use of model plant hosts to identify Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factors". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 (24): 13245–50. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.24.13245. PMID 9371831. PMC 24294. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/94/24/13245.

- ↑ Walker TS, Bais HP, Déziel E, et al. (2004). "Pseudomonas aeruginosa-plant root interactions. Pathogenicity, biofilm formation, and root exudation". Plant Physiol. 134 (1): 320–31. doi:10.1104/pp.103.027888. PMID 14701912. PMC 316311. http://www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/content/full/134/1/320.

- ↑ Mahajan-Miklos S, Tan MW, Rahme LG, Ausubel FM (1999). "Molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence elucidated using a Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Caenorhabditis elegans pathogenesis model". Cell 96 (1): 47–56. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80958-7. PMID 9989496.

- ↑ Martínez C, Pons E, Prats G, León J (2004). "Salicylic acid regulates flowering time and links defence responses and reproductive development". Plant J. 37 (2): 209–17. PMID 14690505.

- ↑ D'Argenio DA, Gallagher LA, Berg CA, Manoil C (2001). "Drosophila as a model host for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection". J. Bacteriol. 183 (4): 1466–71. doi:10.1128/JB.183.4.1466-1471.2001. PMID 11157963.

- ↑ Miyata S, Casey M, Frank DW, Ausubel FM, Drenkard E (2003). "Use of the Galleria mellonella caterpillar as a model host to study the role of the type III secretion system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis". Infect. Immun. 71 (5): 2404–13. doi:10.1128/IAI.71.5.2404-2413.2003. PMID 12704110. PMC 153283. http://iai.asm.org/cgi/content/full/71/5/2404?view=long&pmid=12704110.

- ↑ Rahme LG, Ausubel FM, Cao H, et al. (2000). "Plants and animals share functionally common bacterial virulence factors". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (16): 8815–21. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.16.8815. PMID 10922040. PMC 34017. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/97/16/8815.

- ↑ doi:10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01973.x

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Hachem RY, Chemaly RF, Ahmar CA, et al. (2007). "Colistin is effective in treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cancer patients". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51 (6): 1905–11. doi:10.1128/AAC.01015-06. PMID 17387153.

- ↑ doi:10.1128/AAC.01028-06

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ PMID 14706082 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Kwakman PH, Van den Akker JP, Güçlü A, Aslami H, Binnekade JM, de Boer L, Boszhard L, Paulus F, Middelhoek P, te Velde AA, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Schultz MJ, Zaat SA. Medical-grade honey kills antibiotic-resistant bacteria in vitro and eradicates skin colonization. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Jun 1;46(11):1677-82.

- ↑ Forestier C, Guelon D, Cluytens V, Gillart T, Sirot J, de Champs C. Oral probiotic and prevention of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study in ICU-patients. Crit Care. 2008 May 19;12(3):R69.

- ↑ Döring G, Pier GB (2008). "Vaccines and immunotherapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa". Vaccine 26 (8): 1011–24. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.12.007. PMID 18242792.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||